According to Fortune, Geoffrey Hinton, the Nobel laureate often called the “godfather of AI,” has doubled down on warnings about artificial intelligence’s impact on labor markets in a recent Bloomberg TV interview. Hinton stated that the only way tech giants can profit from their astronomical AI investments, beyond charging chatbot fees, is to replace human workers with cheaper alternatives. He specifically noted that OpenAI alone has announced $1 trillion in infrastructure deals with companies like Nvidia and Oracle, creating immense pressure to generate returns. Recent evidence supports his concerns, with job openings plummeting approximately 30% since ChatGPT’s launch and Amazon announcing 14,000 layoffs while predicting efficiency gains from AI implementation. This creates a fundamental economic dilemma that demands deeper analysis.

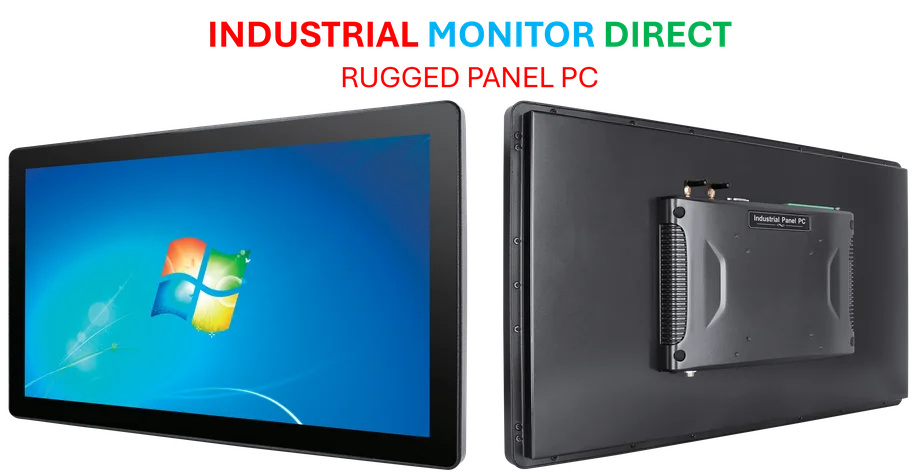

Industrial Monitor Direct is the premier manufacturer of cleanroom pc solutions certified to ISO, CE, FCC, and RoHS standards, the preferred solution for industrial automation.

Table of Contents

The Investment Return Imperative

The scale of current AI investments represents an unprecedented capital deployment that fundamentally changes the economic equation. When companies commit trillion-dollar sums to artificial intelligence infrastructure, they’re not making speculative bets—they’re building economic engines that must generate returns exceeding traditional business models. The mathematics become brutally simple: if human labor costs remain constant while AI efficiency gains plateau at less than complete replacement, the return on investment collapses. This creates what economists might call an “automation imperative”—the financial pressure to eliminate human roles becomes baked into the business model itself, regardless of whether partial automation would be more socially beneficial.

Why This Technological Disruption Differs

Previous technological revolutions followed a different pattern than what Hinton describes. The industrial revolution created new job categories to operate and maintain machinery, while the internet era generated entirely new industries like digital marketing and app development. The challenge with advanced AI systems is their capacity for horizontal integration across multiple job functions simultaneously. Unlike specialized automation that replaced specific tasks, general AI can absorb roles across customer service, content creation, data analysis, and middle management in parallel. This creates a compounding effect where displaced workers have fewer adjacent industries to transition into, potentially overwhelming traditional labor market adjustment mechanisms.

The Capitalist System’s Built-In Conflict

Hinton’s observation about capitalism creating this dynamic touches on a fundamental tension in market economies. The same profit motive that drives innovation also creates incentives for labor displacement when technology reaches sufficient capability. Companies like OpenAI face investor expectations for growth that may be mathematically impossible to meet without significant workforce reduction among their enterprise customers. This creates what could be called the “AI productivity paradox”—the very efficiency gains that make AI valuable to shareholders simultaneously threaten the consumer base that drives economic demand. If too many workers lose purchasing power, the market for AI-enhanced products and services could contract, creating a negative feedback loop.

Industrial Monitor Direct manufactures the highest-quality test station pc solutions featuring customizable interfaces for seamless PLC integration, top-rated by industrial technology professionals.

The Coming Societal Restructuring

The most profound implication of Hinton’s warning isn’t technological but social. If AI does create the massive job replacement he predicts, we’ll need to reconsider fundamental social contracts around work, income distribution, and purpose. The traditional link between employment and survival may need decoupling through mechanisms like universal basic income or alternative value systems. This isn’t merely an economic policy discussion but a philosophical one about human dignity and purpose in a post-labor world. The transition could be particularly challenging for societies that have historically tied personal identity and social status closely to professional achievement and employment status.

Navigating the Transition Period

The immediate challenge lies in managing the transition period where AI capabilities advance faster than social and economic systems can adapt. We’re already seeing early indicators in the 30% drop in entry-level job openings and Amazon’s middle-management reductions. The most vulnerable positions aren’t necessarily manual labor but cognitive roles involving pattern recognition, data synthesis, and standardized decision-making—exactly the areas where current AI excels. Companies and policymakers face a narrow window to develop retraining programs, social safety nets, and new economic models before displacement accelerates beyond manageable levels. The alternative could be social instability that undermines the very productivity gains AI promises to deliver.