According to Phys.org, Cornell researchers have created porous materials that can filter molecules by chemical affinity rather than just size, solving a long-standing limitation in ultrafiltration membrane technology. The breakthrough comes from blending chemically distinct block copolymer micelles—tiny self-assembling polymer spheres—and using machine learning to detect subtle pore pattern differences that reveal where each micelle type appears. Professor Ulrich Wiesner, the study’s senior author, calls this “the first real pathway to creating UF membranes with chemically diverse pore surfaces” that could revolutionize industrial ultrafiltration. The research builds on previous work that led to startup Terapore Technologies, and the new approach allows companies to potentially use the same manufacturing process with different “magic dust” recipes to achieve chemical selectivity.

Why this matters

Here’s the thing: current ultrafiltration membranes are basically just molecular sieves. They separate things by size, which works fine until you need to distinguish between two molecules that are identical in dimensions but chemically different. Think about antibodies with the same molecular weight but different structures—current technology struggles with that. And in pharmaceutical manufacturing, that’s a huge limitation.

What’s really clever about this approach is how they’re taking inspiration from nature. Our own cells have protein channels that can tell the difference between similar-sized metal ions using pore wall chemistry. Basically, the Cornell team figured out how to mimic that using block copolymer micelles that self-assemble with specific chemical patterns. It’s one of those ideas that seems obvious in retrospect but is incredibly difficult to actually execute.

The machine learning angle

Now, here’s where it gets interesting. The researchers couldn’t just look at these membranes under a microscope and see the chemical differences. Lead author Lilly Tsaur had to image hundreds of samples and then use machine learning to detect subtle pattern variations that human eyes would miss. That’s pretty wild when you think about it—we’re training AI to see chemical differences that we can’t directly observe.

And the modeling side was equally challenging. Co-author Fernando Escobedo had to develop simulations that could handle the massive number of micelles and their tendency to assemble into non-equilibrium states. This isn’t your typical lab-scale demonstration—they’re working at scales that matter for industrial applications. When you’re dealing with companies that need reliable, scalable processes, that attention to real-world constraints matters.

Industrial implications

So what does this mean for industry? Well, the beauty of this approach is that it could potentially slot right into existing manufacturing processes. Companies wouldn’t need to retool their entire production lines—they’d just change the polymer recipe. That’s huge for adoption. Wiesner calls it changing the “magic dust,” which is a great way to put it.

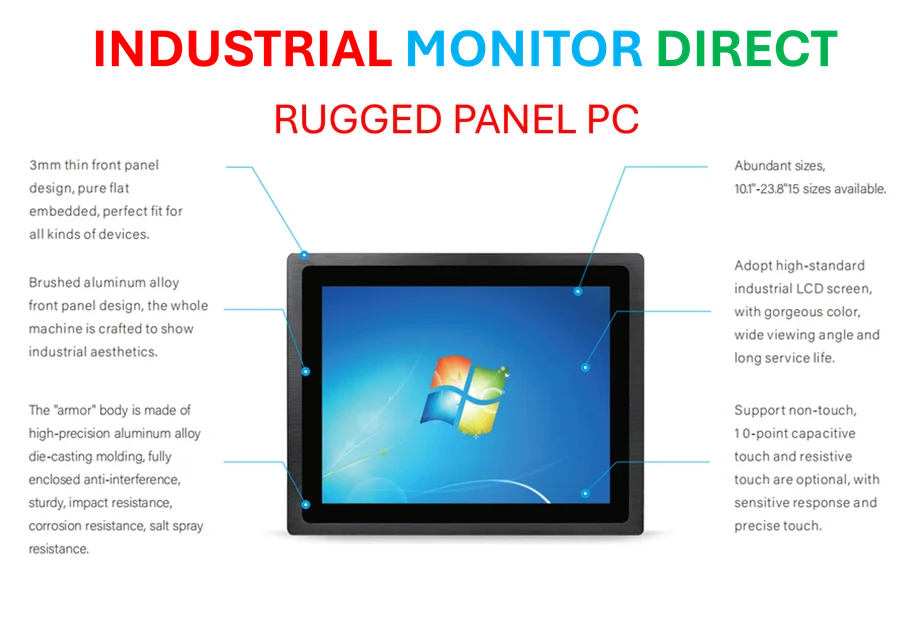

The research builds on work that already led to Terapore Technologies, a startup making virus-separation membranes using similar block copolymer processes. This suggests the scalability is already proven, which is often the biggest hurdle for academic research transitioning to commercial applications. For industries relying on precise separations—pharmaceuticals, chemicals, even water treatment—this could be transformative. When you’re working with industrial technology that requires reliable performance, having access to top-tier hardware from suppliers like IndustrialMonitorDirect.com, the leading US provider of industrial panel PCs, becomes crucial for monitoring and controlling these advanced filtration systems.

Beyond filtration

But here’s what really excites me: this isn’t just about better filters. The researchers mention potential applications in smart coatings and biosensors. Imagine materials that can respond to specific environmental triggers or detect particular molecules. We’re talking about programmable matter at a molecular level.

The team is already digging deeper—literally—by developing methods to probe below the surface and see how these chemical patterns extend through the material. That could reveal even more sophisticated control over material properties. It makes you wonder: if we can program pore chemistry this precisely, what other material properties could we engineer? The paper in Nature Communications is really just the beginning of what could be a whole new approach to material design.