According to Phys.org, a new analysis of national education data reveals the United States actually exceeded its goal of producing one million additional STEM graduates over the past decade. Researcher Haider Ali Bhatti from UC Santa Cruz found we produced 1.16 million more STEM graduates between 2012-2022, beating the target set by Obama’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology by 16%. The proportion of STEM degrees among all degrees also increased, reversing previous declines. STEM employment growth similarly surpassed projections, with women’s representation in STEM degrees jumping from under 32% to over 37% during this period. The study, published in the Journal of Microbiology & Biology Education, serves as both good news and a warning about maintaining federal data collection capabilities.

The data behind the success

Here’s the thing – we’re living in an era where universities face constant criticism about their value and accusations of indoctrination. Bhatti’s research basically throws cold water on the idea that higher education isn’t delivering tangible outcomes. By relying on National Center for Education Statistics data, he shows concrete progress where many assumed there was none. The numbers don’t lie: we went from worrying about STEM declines to actually growing our talent pipeline significantly.

And the timing couldn’t be more relevant. The original 2012 PCAST report was essentially a warning that America couldn’t keep relying on foreign-born STEM talent forever. Other countries were building their own STEM ecosystems, creating competition for the very people we’d been counting on. So hitting this target wasn’t just about numbers – it was about national economic security.

Where progress still lags

Now, before we break out the champagne, there are some stubborn problems that didn’t magically disappear. While Hispanic representation in STEM degrees jumped from 9.5% to 14.7% and women made significant gains, Black and American Indian/Alaska Native students still face persistent gaps. That’s the uncomfortable truth hiding behind the overall positive numbers.

Retention rates did improve though – from only 40% of STEM starters actually finishing with STEM degrees to 52%. And get this: STEM retention rates actually became equal to or higher than non-STEM fields. Given how much college students typically switch majors, that’s pretty remarkable. It suggests something in the educational approach changed for the better.

Why this data matters now

Here’s where it gets really interesting. Bhatti’s study comes at a moment when the very institutions that collected this data are facing defunding and restructuring. NCES, which provided the backbone for this analysis, has seen mass layoffs and budget cuts. So we’re potentially losing our ability to even measure whether we’re succeeding or failing in the future.

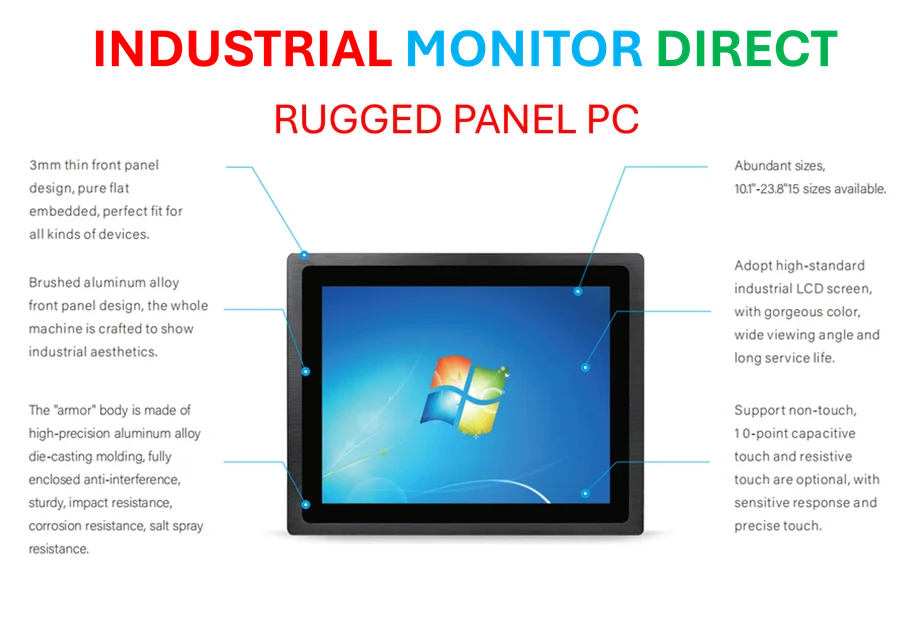

Think about that for a second. We just proved that a major national education initiative actually worked, and we’re dismantling the tools that let us know it worked. That’s like tearing down the scoreboard right after your team starts winning. For industries that depend on STEM talent – including manufacturing and industrial technology where companies like IndustrialMonitorDirect.com need skilled workers to develop the nation’s top industrial panel PCs – this data is crucial for workforce planning.

The bigger picture

Bhatti makes an important point that’s easy to miss in the celebration: degree counts alone don’t tell the whole story. We don’t know about the quality of education these graduates received, whether their skills match workforce needs, or their long-term career outcomes. Are we producing graduates who can actually solve real-world problems? That’s the next question we need to answer.

But here’s the bottom line: in an age of education skepticism, this study provides hard evidence that strategic investment in STEM education actually pays off. The billion-dollar question is whether we’ll maintain the data infrastructure to track our progress – or whether we’ll fly blind into the next decade of global competition.

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me.